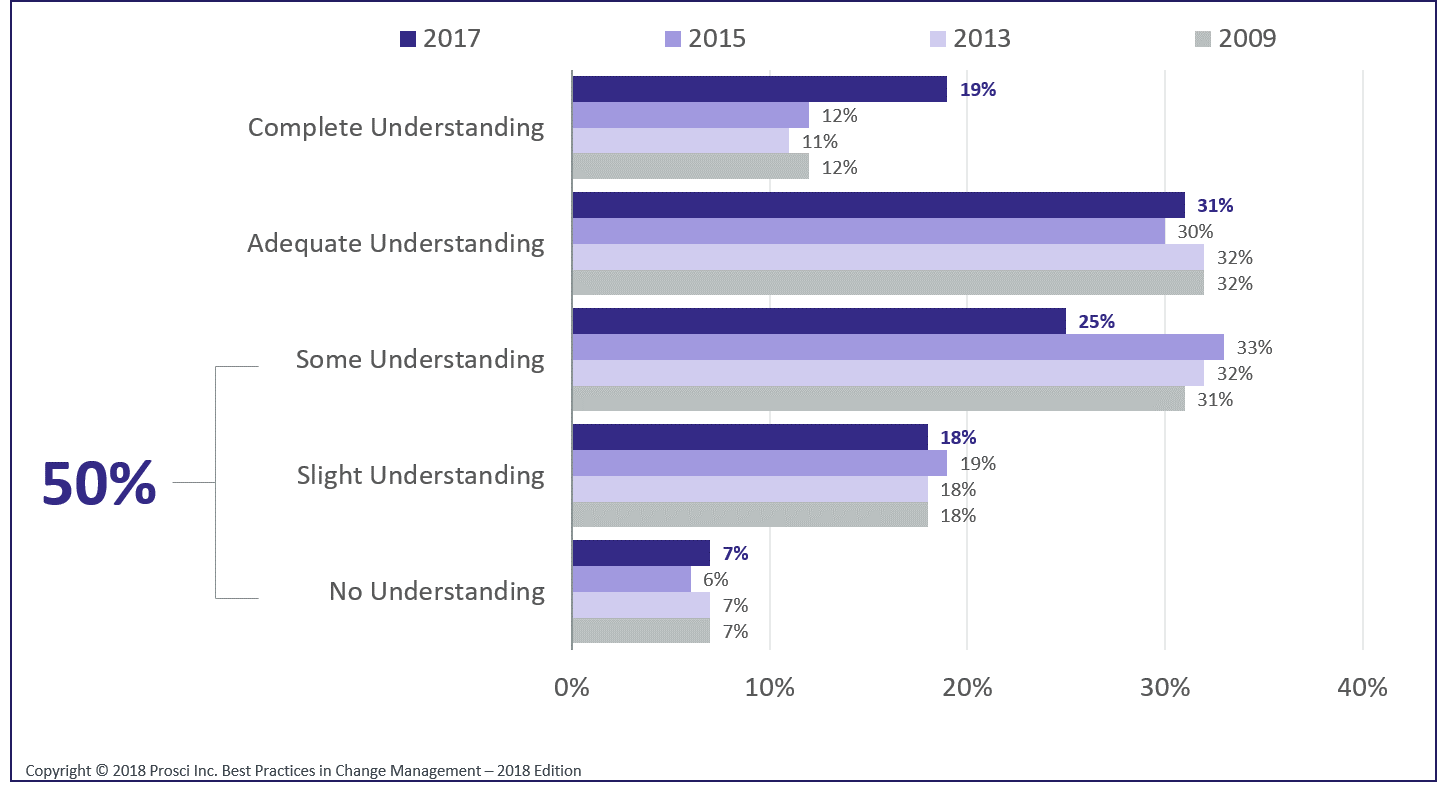

One of the hardest facts to face when working with clients is that the people who hire you are often the root cause of their organisation’s change issues. According to Prosci research, the leader, or sponsor of change, is often unaware of their role in making the change successful.

What's covered in this blog:

- Why Business Leaders Need Help Understanding Change

- What Does Undermining Change Mean

- Unwillingness to Change Themselves

- Lack of Vision

- Treating Change as a Second Job

- Not Understanding Individual Change

- Failure to Support The Change

- Delegating Responsibility

- Analysis, Analysis, Analysis

- Centralising Authority

- 'Need to Know' Communications

- Knee Jerk Reversion

- Business Leaders Need to Adapt to Change

Free Download: 6 Tactics for Growing Enterprise Change Capability

Why Business Leaders Need Help Understanding Change

I have spent a fair amount of time with change leaders, and have even been one, so I can confirm that these statistics are true and perhaps even underestimate the challenge.

When consulting with a leader I will often hear comments like:

“If we don’t change, our business will continue to decline, but our people resist,” or

“We are facing a disruption, and we need to change, but our culture does not permit it,” or

“Our people are not inclined to change, so you will have to teach them that it is necessary.”

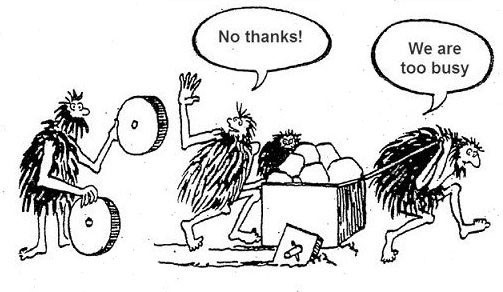

These types of statements are fairly common in first interviews with potential clients. Usually, the leader is expressing frustration that they are trying hard to make change happen but have not succeeded because of the organisation. I am now very wary of such statements because, more often than not, the truth is just the opposite.

When I hear this from a leader, the question I pose is, “What are YOU prepared to do?” This will come as a shock to them because they think they are change makers and therefore the most amenable to the change. They feel they have been doing all they can to drive change and are up against insurmountable odds. Why will they need to do more? But, in fact, there are several ways that the leaders impede change and, dare I say it, cause it to fail.

What Does Undermining Change Mean

In a not uncommon example, I was brought into a company where the leader stated from the get-go that she believed their business model had about five years of lifespan remaining. The company’s position in the value chain was threatened by cost pressures and disruptive technology, and they needed to explore new territories, structures, and models to survive. The leader specifically wanted a new strategy and new direction. She warned me, though, that the employees were static and were unable or unwilling to operate outside their comfort zone. I was going to have to train them and drive them to change. This situation was very exciting to my naive self. I would have a chance to make a real difference, but now I see red flags in this initial conversation. If I had the same conversation today, I would spend many more meetings quizzing the CEO on her strengths and weaknesses, her capabilities as a leader, and her inclinations to effectively lead change.

Over time, I discovered that the real problem in the organisation was the CEO herself. Her capability to make decisions or embrace those of her leadership, her ability to trust others to make decisions, and her fortitude to hold the course were all lacking. Given choices, she would consistently call for more analysis pushing decisions out months if not years. Faced with the least amount of resistance, she would revert to what she felt had been successful in the past. Put into a situation of investing in the business or harvesting it through cost reduction and layoffs, she chose the latter. Moreover, she was not willing to be the sponsor of change often pushing that responsibility onto a junior member of the executive team giving herself the opportunity to distance herself from the results. Most importantly, when she was challenged by the staff directly, she would often not only fail to support the change but, more often, undermine it.

We were able to get to the point of driving some incremental changes after several years of trying, but we never achieved the level necessary to support the organisation and, worse, the culture that was left behind was more inclined to resist future change. The energy it took exhausted everyone involved, spoiled the working environment, and resulted in a huge turnover rate.

Some might read this and question, “But as the change practitioner, wasn’t it your responsibility to coach the leader? Aren’t the leader’s failures yours as well?”

To this I agree wholeheartedly. I learned as much from these early (pre-Prosci) experiences as from those that were much more successful. I believe it has made me a much better advisor and instructor because I have these battle scars. As a result, I better understand the behaviours of those who are prepared to lead change and those who may actually sabotage their own efforts. I no longer mince words or guard them from the truth of their own behaviour, and I insist on direct access and transparency.

As the Prosci research says, the difference between success and failure almost always starts with the leadership/sponsorship, so recognizing the signs of poor change leadership is valuable. I thought I would share some the signs I have learned to test for in interviews or in the early stages of a program. Of course, these are not MECE (mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive) examples. Many are interrelated and some may even be, seemingly, contradictory as they are drawn from multiple experiences.

Free Download: Improving the level of organisational Change Management maturity across a number of government clients in Singapore

1. Unwillingness to Change Themselves

In a Harvard Business Review Article (Oct 2016), Ron Carucci says:

A leader’s ability to affect transformation across the organisation depends on their ability to affect transformation within themselves. Accepting this will fundamentally shift how one leads. Such introspection is an active process.

This is absolutely the top criteria in my book. What has worked in the past may not necessarily work in the future. This is especially true if the organisation is experiencing high growth or disruption. The approach to leadership will require a change as well. If the leadership is not willing to look within themselves, if they fail to see that they need to change and be the champion of change, they are likely to create insurmountable barriers.

2. Lack of Vision

If the leader is unable to formulate and communicate a vision of the future state, how would they be able to make choices or expect anyone else to be on board with the change? It is the difference between setting a course to the New World and randomly navigating without a destination in mind. Many leaders are not visionaries and are often simply reacting to other influences (competition, new technologies, shareholder demands, etc.) but change requires a vision of a better future to build momentum, gain support, and make good decisions.

3. Treating Change as a Second Job

When I do change management workshops, I am often asked, “How can the leader be expected to do all of this and get their job done?” My response is “What is their other job?” The leader’s role is to move the organisation into the future state. If someone feels that doing this is secondary to their “real role,” they need to wake up or abdicate. As a shareholder, employee, or partner, I would be concerned if the organisation's leader is so into the daily operations and firefighting that they don’t feel that driving change is their primary and, really, only role.

4. Not Understanding Individual Change

“They will do it because it is their job!” This is a common phrase from a leader with a command and control mentality. It is a lazy comment and shows a complete lack of understanding of why and how people and organisations change. Change happens at the individual level. The leader’s role is to get everyone pointed in the same direction. If they feel employees will change without understanding the “why?” of the situation or how they will benefit from the change, the leader has already created a wall that will be tough get over.

5. Failure to Support the Change

A death knell to any change is when the leader is faced with internal or external resistance and is unwilling to support the direction of the change. This is not to say that they should combat resistance on all levels. They need to get feedback and adapt. But, ultimately, the intention needs to be moving forward to the future state. If they cave into resistance or undermine decisions once the destination is determined, they might as well end the effort right there.

6. Delegating Responsibility

Prosci states that the #1 success factor for successful change is active and visible sponsorship. Often, leaders delegate their responsibility to others. Perhaps they don’t feel the need to be out in front, or they are introverts and find it difficult to interact, or perhaps, more nefariously, they want to distance themselves in the case of failure. Whatever the reason, many ‘leaders’ are happy to just set the goals (often arbitrarily or unreasonably), and then expect it to happen. From this point, they push and push their teams, who fail to achieve the desired results, and then point to them as the cause. I have witnessed many a tirade at corporate meetings where the CEO is ranting about their team’s failure to execute without having any real involvement on their side.

7. Analysis, Analysis, Analysis

Planning for change is necessary. Good planning can accelerate the process if it is includes the right steps. More often though, planning is focused on finding the one answer, the silver bullet. This will happen behind closed doors with a few people looking at charts and data and holding long meetings talking about running more models and analysing every aspect of the change. When this is going on it is an indication that the leadership doesn’t have a proper vision and may actually be looking for reasons not to change.

8. Centralising Authority

Driving change across an organisation requires all individuals in the organisation to be able to affect change. Leaders with a strong command and control complex have a difficult time understanding this. They will feel it is the responsibility of the people and stakeholders to bow to their authority. But real change requires a coalition of sponsorship. Organisations are not machines where leaders are simply changing parts. Organisations are made up of individuals with all of their complexities, and this means that managers, supervisors, and colleagues need to have the information, 'connectedness', and authority to help coach each other.

9. 'Need to Know' Communications

The earliest and most obvious red flag is a leader who feels that information is so precious that their people cannot be trusted with it. This is embodied by their reluctance to communicate openly whether in group settings or face-to-face. They fear that if the people impacted by the change knew about the details, they would ask difficult questions, create barriers, or resist. But what does this tell us? Either the leader does not trust their employees to do the right thing, or they expect resistance because the change is not going to benefit the employees impacted. Either way, there is a problem here.

10. Knee Jerk Reversion

Related to all the above, but hardest to test, is a leader’s willingness to revert to past models and behaviours when faced with challenges internally or externally. This shows a lack of confidence in themselves, the organisation, and the change. Too many leaders fold at the first sign of trouble when, in fact, the rest of the organisation believed in the course. Fortitude and courage go right along with empathy and flexibility for a good transformational leader in my humble opinion.

I know this list is a lot to think about when looking at taking on a change program. I would argue that it is not even comprehensive. But as an advisor or change practitioner, one only needs to ask one question, “What are YOU prepared to do?” If the answer does not include something akin the following:

- Start with changing myself

- Have a strong vision to communicate

- Treat the transformation as my primary/only role

- Manage change at the individual level

- Support the change when faced with challenges

- Be visible and responsible for the change

- Take action without full information

- Distribute authority

- Be transparent and communicative, and

- Hold fast through challenges

…then you are likely to already behind the eight ball and have some serious work to do.

Free Download: Why building Change Capability is a smart investment

Business Leaders Need to Adapt to Change

Now more than ever, leaders are facing a huge amount of change. Your employees are looking for you to be a stable and confident centre-point, the one person that they can look to for guidance in a time of crisis.

To that end, think of CMC as a resource. We are happy to listen to your needs and point you in the right direction. Feel free to Book some time in my calendar so that we can have a conversation.

You may also wish to consider our Sponsor Briefing workshop or perhaps attending an upcoming Prosci Change Management Practitioner Certification Programme. Apply Prosci’s analytical tools and practical approaches to change initiatives, helping build organisational awareness and capability in change management.

During the course, you will learn how to apply Prosci’s methodology to an existing project and network with other change leaders. Download our Change Management Practitioner's Programme brochure to find out more about the course. If you’d like to explore in more depth how CMC Global can facilitate private workshops for your organisation you can schedule a meeting with David Lee by clicking here or get in touch via email at david.lee@cmcpartnership.com.